justin like the song: "Fake"

I wanna start by reminding y’all that I’m staking a claim for a best track on an album that broke through to herald a notorious genre in the year of Superunknown, The Downward Spiral, Illmatic, CrazySexyCool, Southernplaylisticadillacmuzik, My Life, Protection, Jar of Flies, Welcome to Sky Valley, Live Through This, and Dummy.

The case for “Fake” is a case for versatility, virtuosity (in the context of Korn’s musicianship, I know this word choice is a huge risk but I’m confident), surprise, and promise: a medley of what the band can do well, what risks they had not yet taken on the album, and what they might pull off on future efforts and transform into a distinct range. This is nearly my same defense of “With You” for Hybrid Theory’s best, except that Korn’s degree of give-a-fuck was comparatively squat. It’s not like Korn announces itself as a pick-me LP, and “Fake” gets little credit among so many indelible dark delights but on this one they were really in their bag.

Because Korn’s bag is, or was, essentially something like a suicide party on a mudslide under a new moon. Their rock set itself apart as not rap-hyphen, it stank so much even grunge couldn’t approach it, and it was too unintelligible to be gatekept. Thirty years ago Korn debuted a dire yet dynamic, irreverent, seven-stringed, West Coast-decadent breed of metal, undergirded by a fat-assed bass before the advent of trap and a drummer so stylish no drum machine could mimic.

In my mind any stamped Korn standard has to be to some degree a dance track. “Fake” starts out that way, but if it were a slasher film, the first riff would be a false protagonist who gets killed after we get used to seeing her on screen. Deftones purist fans who read this will say they accomplish this dichotomy best (and with "Chi", that was true), but in 1994 Korn had to show on this arrival that they came to break faces but also get over nothing and also keep partying.

In the wake of tracks like “Clown” and “Faget,” which totally exploit the expressive capacity of single riffs to tremendous effects, and then the singular “Shoots and Ladders,” which got metalheads hype for bagpipes and then made us mosh to nursery rhymes, “Fake” is a B-sider that maybe does too much too mutely. It isn’t especially memorable given its company, but I’d say that’s because it’s holding the memory for the rest of the album; this song operates more like an archive than a text. Structurally it alternates four or five riffs/arrangements that initially pretend to adhere to a form until that form gets kinda pulverized at the halfway point, and from then on it’s a good mess of Korn’s early innovative play in which the density and volume are jump scares. (I grieve this formally subversive version of Korn.) “Fake” is the best track here because, in the album sequence, it has so little to lose or to prove, leaving the guys room to experiment playfully and not diminish play or experimentation by chasing catchiness. It bursts with Korn’s forthcoming trademarks: a giant low-end groove, Head and Munky ping-ponging notes and exchanging octaves, Jonathan’s being deeply antisocial and directly a hater (is there a more inviting utterance of I can’t stand the sight of you?) and then scatting, and Silveria and Fieldy building a rhythm section out of synchronic 16ths where the bass is also drums and the drums sometimes revel in non-sequitur mood-swing cadences.

It also promises that shit gets darker. There’s a part in this song, at about 1:30, that sounds like all the instruments just get curb-stomped and the distortion bleeds and it is ominous all hell and you think they wouldn’t try to use it twice, but then it returns having lost no potency, and by the third time the walls of this track ought to be obliterated but what’s probably bleeding now are Jonathan’s vocal cords. But nah, there are more corners to round before “Fake” ends, and at the moment I’m writing this my heart breaks at never getting to see this band live when they had this much chaotic energy and audacity.

Gabi Brown: "Blind"

Y’all. It’s “Blind.”

It starts with a quiet, insistent ride cymbal hitting 16ths, the last 4 notes in the measure higher and muted, hinting at something to come. A guitar sliding into the promised opening, all jagged-edged flange and dissonance. A few notes from a bass, a familiar R&B cadence but downright sinister against the anxious guitar and persistent rapid-fire cymbal. Anything could happen next–the building blocks are all here and all that remains is to find out how the band slots the bricks together.

Okay, look, so an 0-2-0-3 riff isn’t anything special. It’s the kind of lick you come up with jamming alone in your parents’ basement, captivated for a blissful minute with the tension between the root and minor second before moving on to try to learn the stuff that’s supposed to grab your attention. But Korn teases the riff, Jonathan Davis asks–no, demands–if we’re ready, and then the whole band fucking commits.

It’s not complicated. And it doesn’t have to be. But in the universe the band’s creating, a universe deeply indebted to ancient musical traditions, it has to groove. You have to feel the ebb and flow and the spaces between notes in your body, stop on a dime before the rhythm comes back like an answered prayer.

Of all the songs on Korn’s debut, this is the one I keep coming back to the most. It’s the hypnotic simplicity of that opening bounce riff, and the way the band locks in as they dance between four notes. Nothing else on the album comes close to that level of jouissance–sure, it’s lyrically dark as any of the tracks that follow, but it’s also fun as hell.

For me, that’s the essence of nu metal. The duality of our inner emotional turmoil and the need to get the fuck up, keep moving, maybe shake a little ass, idk, I’m not your mom. Whatever gives you the pep in your step to get through another day, another year.

“Blind” nails it. It makes a lot of promises and then delivers, in a way that so many bands have tried to capture since and so few have achieved.

So yeah. It’s “Blind.” “Blind” is the one.

Lucia Z. Liner: "Faget"

Without pointing any fingers or naming any names, nu metal gets a frat boy reputation from some less knowledgeable music fans. The swagger and braggadocio of hip-hop mixed with the one-upmanship of metal may not always result in the most welcoming environment. What gets forgotten is the sense of belonging that heavy metal brings, a union of the outliers, the weirdos of the world. The people who don’t look, talk, walk, act like everyone else. The ones who get written off and pigeonholed.

It is from this angsty spirit which “Faget” comes from. Jonathan talks about wearing makeup and being a huge Duran Duran fan, and so he was labeled as a sissy, queer, insert pejorative term here. What he then does with the song is something transgressive given the late Nineties, a time where that word was thrown around at will in popular culture. Rather than fight back against the allegations, as if being gay was a bad thing, he highlights the internal struggle he felt from the label. They don’t understand, they’ll never understand… but what if they’re actually right?

This is a relatable song on so many levels, only in my case, the label wasn’t inaccurate. What are you gonna do, am I right? In an odd way, it’s sort of reclamation of the slur, and I’m not saying that Jon Davis gets an F-slur pass, but I wouldn’t be against the idea either. It’s using the power of words against those that levy that power against you. If they can’t hurt you, they lose, and the lyrics show that Jon or whatever persona he’s given this song are in enough pain, enough angst, that whatever labels his peers are putting on him aren’t cutting as deep as they would hope.

Jarring as the sight of the intentionally-misspelled word might be when first reading the track listing, “Faget” is a powerful statement piece in terms of identity and the power we give words, both subjects that would go on to define alternative music forevermore.

Timon De Zwaef: "Clown"

“Once we started playing, there was a complete sense of concentration among all of us. It was truly the only time we were all focused,” said Fieldy, Korn’s unofficial bassist, about the band’s recording process. Fieldy hasn’t always been known for his integrity, but there’s no denying the truth in what he said. That collective focus, all five members locking in somewhere in the hills of Malibu, becomes immediately apparent in the opening segment of “Clown,” the fourth track and single from their self-titled debut album.

“Duh Nuh Nuh- EERRRHHH!!! Duh Nuh Nuh- EEERRUHHHH!!!”

“Hey, are you saying so there’s no clicks?”

“We’re recording! Start!”

“Just fucking do it, dammit!”

“Clown” is a prime example of Korn’s ability to create a bleak, unsettling atmosphere without trying too hard. After 43 seconds of playful band-vs-producer banter, you’re greeted by four of those gnarly “Duh Nuh Nuh- EERRRHHH!!!” riffs that Munky teases in the intro. Only this time, instead of making you chuckle, they plunge you into a disgusting journey through one of Jonathan Davis’s personal traumas—par for the course when it comes to Korn's music. “Clown” is about the time a skinhead tried to punch Davis after telling him to “fuck off back to Bakersfield.” What follows is an explosion of ugly, frustrated emotions that reverberate throughout the entire album.

More than anything, it’s Davis’s delivery of these emotions that set him apart from other metal vocalists in 1994. Sure, war, corruption, and injustice are important topics to tackle, but Davis understood something deeper: songs about personal trauma—messy, relatable pain—are what make a crowd stay, move, and connect.

Sputnikmusic praised Davis’s voice as the key to Korn’s uniqueness, and while I agree, they missed mentioning the other elements that cemented Korn as pioneers of a new movement in heavy music. “Clown” showcases those elements better than any other track on the record. Fieldy’s rattling, almost nausea-inducing bass tone, those sleazy, barely-in-tune guitars, and one of the crispest snare sounds you'll ever hear. Head and Munky also flex their signature yin-and-yang dynamic in the verses, trading off between eerie scratch-like noises and a menacing, Mr. Bungle-inspired riff. Together, it all forms this twisted Pandora’s Box of sound—one that would be deconstructed and reassembled countless times, both by Korn themselves and the wave of bands that followed. It’s baffling how Korn could sound so strung out yet so ridiculously tight at the same time.

The music video for “Clown” is a fever dream in its own right, almost as if Davis directed it himself. It even features those creepy dolls that would later hang from the ceilings during mid-'90s Korn shows. Whatever you think of the video, it left quite an impression on a young Corey Taylor. And fun fact—the song reportedly inspired Korn to write “Twist.” But that’s a story for 2026.

Josh Rioux: "Daddy"

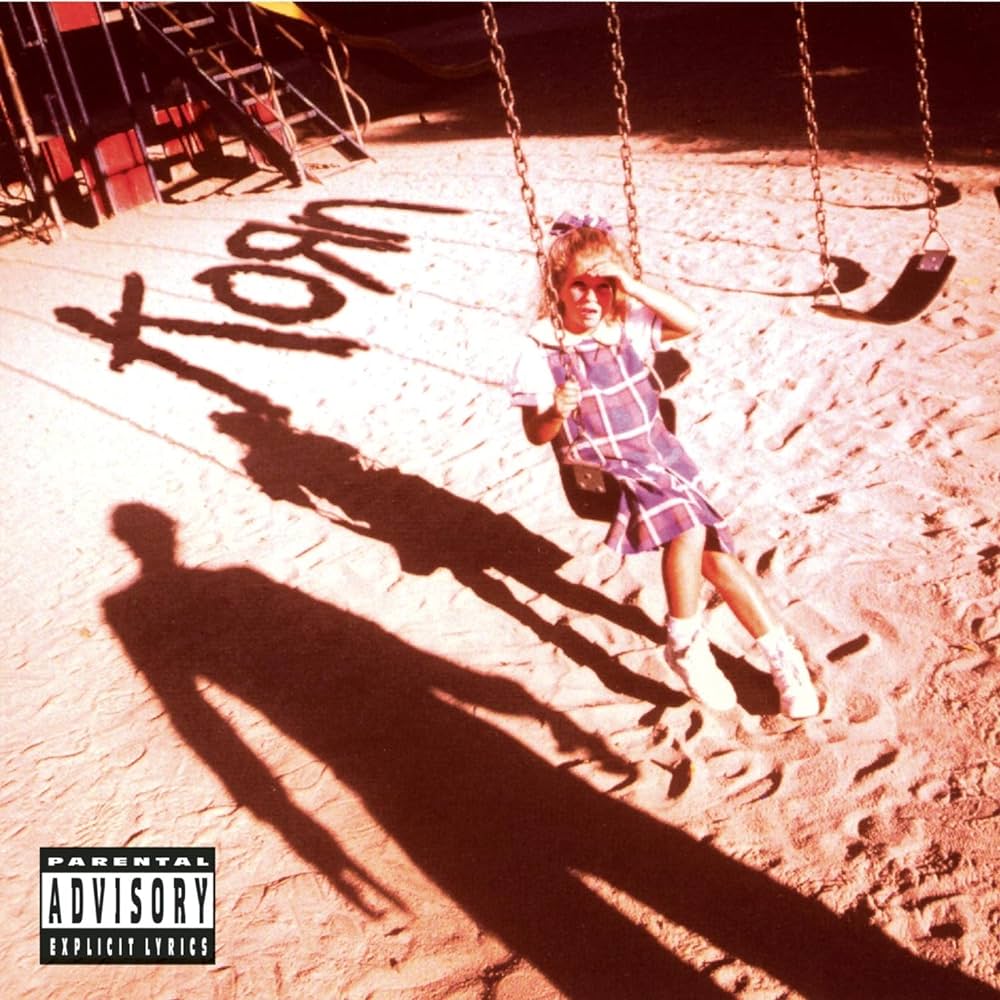

An album cover makes a promise that the record itself may or may not keep. By 1994, the record-browsing public had had a good 3 years of alt-rock cover art trading-in the traditional rock star peacocking and bitchin’ tattoo inspos for the fresher options of irony, goofery, or other kinds of beauty–long enough to get familiar with the subtext that what lay within was something other than girls girls girls or jungles as metaphors for that big crazy city, but not so long that the church kids had started using it to trick us into thinking they were mad about the same shit as we were. Picking up Dookie, you might have thought, hellyeah, maybe it would be fun to have a giant poo battle. Blood Sugar Sex Magic? What would it be like if we all did acid and licked each other at the same time?

But a kid on a swing in calm-before-the-twister lighting and a Babadook-ass shadow falling across the playground sand? And on the back cover, the playground again but the kid and the shadow are gone? It’s the kind of promise that, if the band makes good on it, feels like the kind of thing you won’t be able to put all the way back on the shelf after. From “Blind”’s opening challenge “Are you ready?”, through the wounded bile of “Faget” and the nursery-rhyme nightmares of “Shoots and Ladders”, that cover image sits like an unspoken secret you’re not quite ready to discover, not just an elephant in the room, but one that’s wearing the scariest mask you’ve never seen. “Daddy” is the elephant in the room.

You’re not going to head bang to this one. You’re not going to sing along–at least not if you know the words. But “Daddy” is the song that takes Korn from Illmatic-style assembly-line of bangers to the kind of epocal record that remains a totemic cult object of mystery and worship regardless of how many units shift and how many streams pile up. While the record’s previous 11 tracks demonstrate what Korn was capable of in 1994–raw, primal funk metal with snaky, soiled grooves and a frontman so wildly emotive and dynamic that he didn’t so much move between voices as he did channel personalities, as many as four or five within a single song–”Daddy” is Korn and Davis arriving at the swirling black pit from which this band’s shocking rawness and originality seeps. Less a song than a therapy session-cum-exorcism on tape, “Daddy” sees Davis confront his sexual abuse at the hands of a parental figure as a child over approximately nine-and-a-half minutes that begin with the singer’s most definitionally beautiful vocals on the record and ends with him violently sobbing in the vocal booth as the band seemingly improv a sober coda to what feels like a monumental ritual of cleansing. With everything that happens on this record telling you there’s something behind the closet door, somehow nothing prepares you for what happens in between those moments. Coming out of a genre that often played with concepts of the forbidden, “Daddy” actually feels like something you maybe shouldn’t have been allowed to hear, and it’s hard to listen to as an adult without wondering at the choice made to expose Davis this way. Ethical and personal considerations aside, there’s no denying its, and Korn’s, power, even at this very earliest stage of their career.

“Daddy” closes the record that opened the door on a new genre that would go on to confront the damage done to youth by a rapidly sickening culture using grooves and riffs so freshly sick that a new language of rock had to be invented to accomplish it. That process of invention begins on Korn, but the necessity for its invention is in “Daddy”. In the end, I guess that pretty much answers any lingering questions, although I can’t promise the discomfort will pass any faster.